The idea of a $3 nutritious meal is appealing. It signals compassion, efficiency, and a desire to make healthy food accessible to everyone. In an era of rising food prices and widespread diet-related illness, the intention behind the proposal is understandable.

But intention isn’t the same as feasibility. When you step back and look at the actual economics of food — from farming to processing to cooking — the $3 meal quickly stops being a solution and starts looking like a slogan.

A $5 meal, on the other hand, is far more realistic. And realism matters if the goal is to improve health rather than just win headlines.

Where the $3 meal breaks down

At $3, there are only a few ways to make the math work — and none of them are good. To hit that price point, food must be:

-Highly subsidized

-Highly processed

-Produced at massive industrial scale

Or often, all three.

That usually adds up to refined grains, seed oils, added sugars, artificial flavoring, and cheap protein isolates. Calories can be delivered for $3 — nutrition cannot.

The result is food that technically feeds people but continues to drive metabolic disease, obesity, diabetes, and chronic inflammation. These are the very problems food policy is supposed to reduce.

The hidden cost of “cheap” food

A $3 meal doesn’t eliminate cost — it externalizes it. The bill simply shows up later in the form of:

-Higher healthcare spending

-Lost productivity

-Increased dependency

-Long-term disease management

We’ve already run this experiment. Ultra-cheap food has been widely available for decades and the result hasn’t been a healthier population. It’s been the opposite.

If low cost alone were the answer, the problem would already be solved.

Why $5 changes the equation

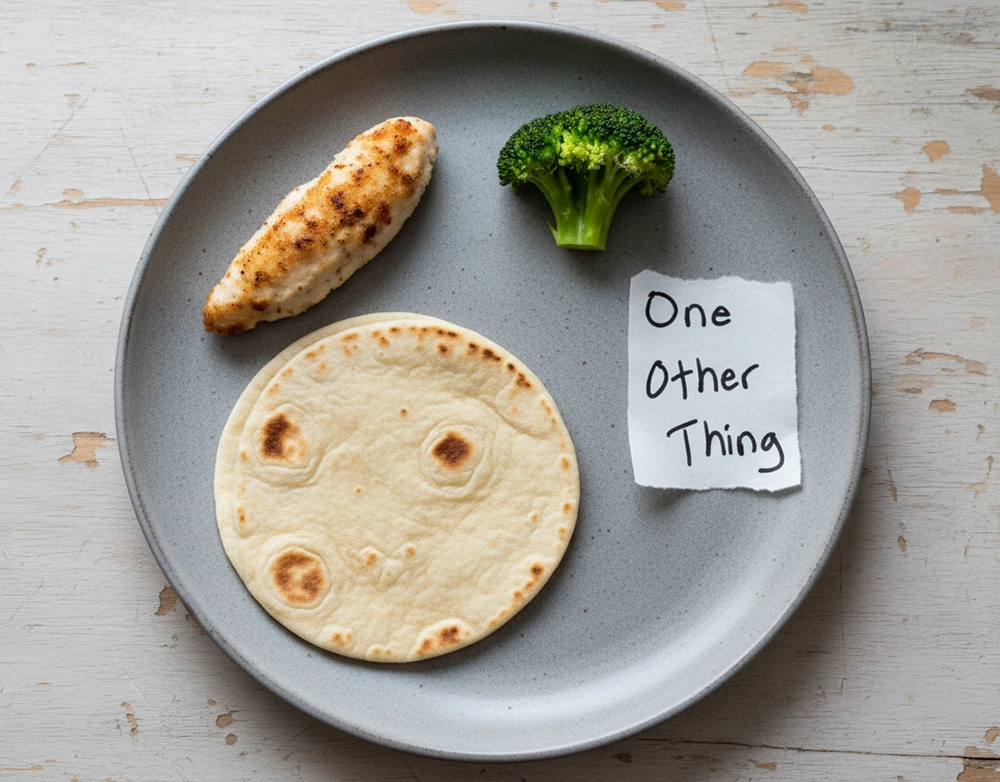

At $5, the landscape shifts meaningfully. That additional $2 allows for:

-Real protein (eggs, dairy, meat, legumes)

-Whole ingredients instead of engineered ones

-Fats that hold up under heat

-Improved preparation without industrial shortcuts

It also allows farmers, producers, and kitchens to operate without being forced into unsustainable margins. A $5 meal doesn’t require miracles — it requires basic economic honesty.

Nutrition improves on a curve, not in jumps

It’s also worth acknowledging that nutrition doesn’t improve in fixed jumps — it improves on a curve. Every dollar above the bare minimum allows for meaningful gains in food quality, preparation, and economic stability.

At the low end, small increases have outsized impact: better protein, better fats, fewer industrial shortcuts, and greater resilience in local food systems. Returns eventually taper as spending rises, but at $3 we’re still far below the point where real nutrition is even possible.

In that sense, the question isn’t whether $5 is “perfect,” but whether it represents a realistic starting point that allows health to improve rather than degrade.

Calories are not the problem

One of the most persistent mistakes in food policy is treating nutrition as a calorie problem instead of a biological systems problem. People aren’t sick because they lack calories. They’re sick because their bodies lack adequate protein quality, essential minerals, stable fats, hydration, and metabolic flexibility.

You can meet calorie targets cheaply. You can’t rebuild health cheaply.

A $5 framework at least acknowledges this reality.

Labor, cooking, and time matter too

Food doesn’t exist in a vacuum. It exists in kitchens, supply chains, and communities.

At $3:

-Labor is squeezed

-Cooking quality declines

-Safety margins shrink

-Centralized mass production becomes mandatory

At $5:

-Local preparation becomes feasible

-School kitchens and community programs can function

-Simple, repeatable meals make sense

Ignoring labor and preparation costs doesn’t make them disappear — it just degrades outcomes.

A better question to ask

Instead of asking, “What’s the cheapest possible meal?”, we should be asking, “What’s the lowest-cost meal that actually improves health outcomes?”

That’s a very different question. The first question leads to shortcuts. The second leads to sustainability.

The bottom line

The $3 meal is a well-intentioned idea that underestimates the complexity of food systems and human health. It risks repeating the same mistakes that created today’s nutrition crisis.

A $5 meal isn’t perfect — but it’s honest. It recognizes that:

-Real food costs money

-Health can’t be engineered on the cheap

-Prevention is less expensive than treatment

-Nutrition policy must be biologically grounded, not just economically optimistic

If the goal is to reduce disease rather than simply reduce hunger, realism beats symbolism every time.

Written By Benjamin Smith

Benjamin Smith is Founder and CEO of Ultimate Health Model, a disruptive approach that addresses underlying reasons for health issues. He’s a certified health coach with a passion for sharing information to help people get well. His new book, Why Are You Sick? How to Reclaim Your Health with the Ultimate Health ModelTM(Pro Audio Voices, Inc., Aug. 20, 2025), empowers readers to not just survive, but thrive. For consulting services and to learn more go to ultimatehealthmodel.com. Link to his free audiobook here.